Briefing 1: Access to Work and Residence Permits for non-EU workers

Thomas Huddleston | 14. 2. 13Despite openings in recent years, perhaps the biggest hurdle for all categories of non-EU workers across most countries is identifying the ‘needs’ on the labour market for work immigration. EU countries with little history of work immigration, including those in Central Europe, traditionally have had only one general immigration regime for all immigrant workers whereas more established countries of immigration like France, Germany, and the UK often have a highly complex set of rules for different categories of workers. Furthermore, many countries restrict the eligibility of employers to access the application procedure for a particular scheme. Consultation with employers and trade unions is rarely the basis for adjusting labour market tests, shortage lists, or quotas. In many countries, the government formulates and institutes these decisions unilaterally by executive decision. This state-driven process may not be as effective or transparent for identifying labour market needs, responding rapidly to changes, or building awareness and consensus about work immigration opportunities.

GENERAL CATEGORIES OF MIGRANT WORKERS

General categories of non-EU migrant workers face contradictory policies in most new immigration countries in Central and Southeast Europe (so-called EU12 countries), according to the results of the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX). In many of these countries, ordinary non-EU workers can access many forms of public support, such as public employment services, education and training. However, there is hardly any targeted job or training support, which is indeed an area of weakness across Europe. ‘Brain waste’ is another weakness for labour market mobility, since they face less favourable procedures than EU nationals to recognise their non-EU qualifications and skills. Non-EU newcomers often cannot use all forms of social security that they pay for as taxpayers. Few have yet adapted public job services to serve migrants or facilitated recognition of non-EU degrees. Often in Central Europe, non-EU temporary workers cannot access the public sector or cannot change jobs or sectors like EU citizens can.

Near-equal workers’ rights and general support for all workers is favourable for all workers not only to be treated equally in the workplace, but also to invest in the new skills and jobs that Europe needs to grow in the future. Directives guarantee long-term residents, reunited family members, and a few other groups at least equal access to employment, general support, and equal workers’ rights. The fact that most other migrant workers are not addressed in current EU law directly affects their labour market opportunities in many EU Member States, particularly in EU12. Over the past few years, new immigration countries are catching up on equal access and general support, largely because of EU obligations.

The 2011 EU Single Residence and Work Permit, the EU’s major achievement to date on the rights of migrant workers, will improve the legal situation in nearly all EU Member States, if properly transposed at national level. This Directive provides a single permit for general non-EU workers to residence and work as well as a common set of equal rights for these workers. During the negotiation, Member States did water down several provisions and limited the scope, role of different authorities, and the requirements for the procedure and fees. For example, single permit holders can only exercise the authorised employment activity, while self-employed workers are excluded from the scope, among others. Furthermore, mechanisms to enforce the rights of legal non-EU migrant workers remain rather weak. In comparison, the Employer Sanctions Directive (2009/52/EC), which only applies to irregular migrant workers, encourages strong and regular inspection mechanisms and guarantees the right to complaints’ mechanisms and payment of outstanding wages.

The Directive’s greatest achievements are access to general support and equal workers’ rights for single permit holders. Most non-EU citizens on general work permits would need to receive equal treatment in terms of their access to general support and workers’ rights, with only a few restrictions allowed. Article 12 grants them equal access to general support and equal workers' rights. In many countries non-EU workers would enjoy significantly better access to public employment services, qualification recognition, social security, and information on their rights. The deadline for transposition is 25 December 2013. According to my MIPEX impact assessment, proper transposition would lead to important improvements in new immigration countries in Central and Southeast Europe, especially Latvia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Cyprus.

THE ‘BLUE CARD’

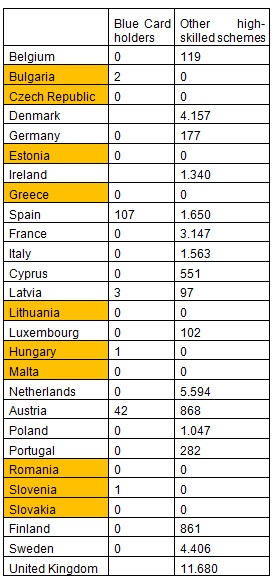

New permits for high-skilled work, 2011, Eurostat

The EU Blue Card harmonises the conditions of entry and residence of non-EU citizens for highly-skilled employment. Positively, the directive guarantees their rights, family reunification, and EU mobility, which could make the EU easier to access and more attractive in the global competition for talent. Member States had to transpose the Directive by June 2011.

Significantly, no other highly-skilled migrant worker scheme exists besides the Blue Card in several Member States, especially in Central and Southeastern Europe. Most Central and Southeastern European countries – with rare exceptions like the Czech Republic and Lithuania – only had one scheme that applied across the board (generally in an unsophisticated manner) to all temporary migrant workers before implementation of the EU Blue Card.

The creation of a specific Blue Card scheme in many EU12 countries has improved the legal opportunities for highly-skilled immigrants. Research undertaken by MPG finds that Blue Card holders or other highly-skilled migrant workers tend to have more rights and a more secure status than ordinary migrant workers in most EU countries, including Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Slovenia. The greatest difference is the right to remain for a specific time-period in case of unemployment. Highly-skilled migrant workers also tend to enjoy permits of longer duration, greater access to vocational training, higher education, and family reunification.

At this point, it is unclear how the Directive will impact highly-skilled migration to the EU. Admission decisions remain in the hands of the Member States, who decide whether and how many to admit on a Blue Card or on other national schemes. In 2011—the first year of the Blue Card’s implementation, hardly any Blue Cards were issued in just a dozen Member States (see adjacent Eurostat statistics). More broadly, no highly-skilled workers were admitted under the Blue Card or another scheme in most of the Central and Southeast European countries, highlighted here in orange: Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Lithuania, Malta, Romania, and Slovakia (just one in Hungary and Slovenia and two in Bulgaria).

ONGOING DISCUSSIONS: INTRA-CORPORATE TRANSFERS AND SEASONAL WORKERS

Member States are currently negotiating two directives on the conditions of entry and residence of non-EU citizens for the purposes of seasonal employment and in the framework of an intra-corporate transfer (a.k.a. ICT). The special procedure set out for seasonal workers not only aims at fair and transparent rules for these workers, but also incentives to “prevent a temporary stay from becoming permanent.” Member States have been discussing the nature and duration of their legal status as well as limitations on the rights of seasonal workers (e.g. social security, housing). The ICT proposal aims to streamline the procedure for companies, who face 27 different procedures in each of the Member States. Debate on this proposal has mostly focused on reinforcing the temporary nature of ICT, setting qualification requirements fighting potential abuse of this channel.

QUESTIONS

How has your country recently changed its policy on the access and rights of non-EU migrant workers?

- Which mechanism does the state use to control the number of newcomer migrant workers?

- Does the state use preference system? What impact it has on migrants?

How does the state evaluate the need of the labour market?

- Are employers and trade unions interested and relevant to open to non-EU work immigration? What policy role are they playing to identifying shortages on the labour market?

How can your country tackle problems of unequal or unfair working conditions in practice while opening equal access to non-EU residents?

What targeted supports do immigrant workers need in your country to improve their skills and obtain jobs that meet their qualifications? Are there any past projects that could serve as a model for national policies?

The article has been written as part of the project Migration to the Centre supported by the European Commission - The "Europe for citizens" programme, and the International Visegrad Fund.

This article reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

Thomas Huddleston is a policy analyst at Migration Policy Group, working on the Diversity & Integration Programme. His focus includes European and national integration policies and he is the Central Research Coordinator of the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX).